Chronic fatigue syndrome, also known as myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME), is a complex, multi-system condition that affects 2-4 per 1,000 New Zealanders.1

This MedCase describes a typical case of CFS/ME encountered in general practice with a focus on management ideas around caring for these complex patients.

Miss C is a 17-year-old girl who comes to see you with a two-day history of worsening tiredness, pelvic pain, and difficulty sleeping. She has run out of tramadol, which she uses in addition to paracetamol for pain exacerbations.

Miss C feels extremely tired and tells you she has been bedbound for the past few days since she attended three full days of school in a row.

Her sleep is poor, with multiple night-time waking. She has tried zopiclone and melatonin with little improvement. She sleeps for over 12 hours at other times but wakes feeling unrefreshed, requiring naps during the daytime. Usually, her tiredness means that she can't manage full days at school, but she attempted to go this week as they are preparing for exams.

Pelvic pain is a chronic problem that started around 12 months ago and is present most days, usually at a manageable level but with occasional exacerbations that are only partially relieved by tramadol. The exacerbations often occur after she has been busy or stressed.

Miss C has been seen multiple times over the past 18 months. Things began after infection with likely infectious mononucleosis; subsequent blood testing showed Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) seropositivity. The fatigue persisted, and the pelvic pain and sleep problems gradually worsened. Miss C has also experienced other intermittent symptoms, including low mood, weight gain, intermittent loose bowels, and abdominal pain.

Previous notes document repeated normal examination findings and no significantly abnormal blood test results. Miss C has seen several secondary care services, including:

- Gynaecology for pelvic pain, with no evidence of polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) and no abnormalities on pelvic ultrasound. The combined oral contraceptive pill (COCP) was started, with no effect on the pain.

- Gastroenterology for abdominal pain and irregular bowel habit. Endoscopy was normal and a diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) was suggested.

- Rheumatology for intermittent neck and abdominal plus a positive antinuclear antibody (ANA) result, with no evidence of inflammatory arthritis. Fibromyalgia was considered but the diagnostic criteria were not met.

Today, Miss C is here with her mother. They are both frustrated at the ongoing impact of Miss C’s symptoms on her life. Miss C was previously an enthusiastic and high-achieving student at the local high school. However, this year she has missed a lot of school and will be unable to sit her year-end exams. She has also had to stop her dance lessons and quit the netball team.

How do you approach this consultation?

Could this be CFS/ME?

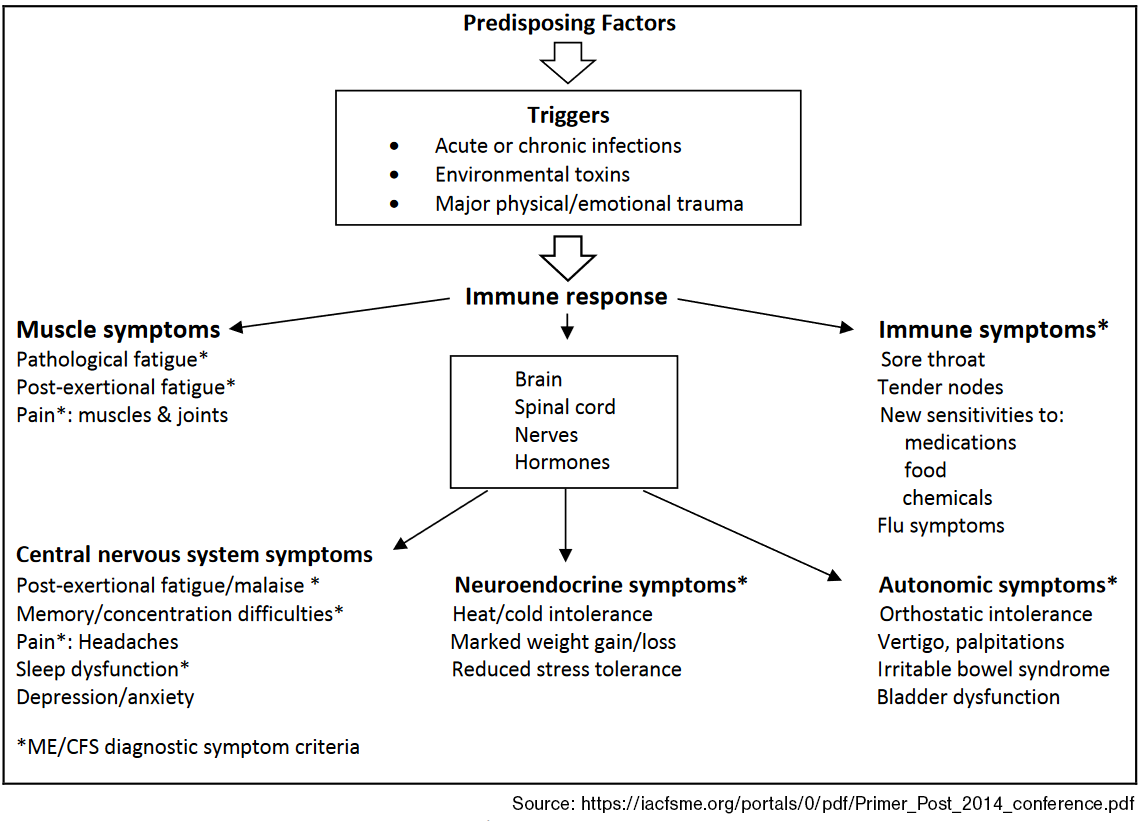

Yes. Miss C has described several of the neuroendocrine, cognitive, autonomic, immune, and metabolic changes that characterise CFS/ME (Figure 1).1,2

Figure 1. Multisystem Dysregulation in ME/CFS

Diagnosis requires careful analysis of the patient's history and pattern of symptoms, plus exclusion of other fatiguing illnesses.1 The BMJ Best Practice suggests several criteria, although clinicians do not always adhere to all four. These are: A diagnosis of ME/CFS should be suspected if the patient has all four key symptoms (e.g., post-exertional malaise, debilitating fatigue, cognitive difficulties, unrefreshing sleep or sleep disturbance) for a minimum of 6 weeks in adults and four weeks in children and young people.

There are no specific examination findings, though some subtle signs may assist in diagnosis (ref Figure 1).

Basic laboratory testing is indicated initially to look for other causes (e.g. chest x-ray for cough). Symptoms should guide more specific testing, but no specific diagnostic findings exist.

Practice points

Diagnosing CFS/ME

- Consider CFS/ME in patients with prolonged fatigue and other typical symptoms following an acute initial illness (though gradual onset is also possible).

- Exclude other fatiguing illnesses by investigating based on symptoms as appropriate; an alternative diagnosis can be found in up to 1/3 of likely CFS/ME cases.

- The key features that usually distinguish CFS/ME from other fatiguing illnesses are:

- post-exertional malaise (PEM) (immediately or delayed 24 hours or more)

- symptom exacerbations in response to stressors (physical or mental overexertion, new infections, sleep deprivation, immunisations, or other medical comorbidities).

You raise the idea of CFS/ME and explain to Miss C you would like to assess her symptoms using the Clinical Diagnostic Criteria worksheet.

The results suggest that she meets the diagnostic criteria. You agree that this seems likely in view of her other results and negative findings on previous investigations.

What do you do next?

Establish a collaborative therapeutic relationship

Making the diagnosis can provide relief for patients, who have often been living with difficult and unexplained symptoms for some time.1

Offering information about the biological changes underpinning the symptoms can help patients and their families understand and accept the diagnosis.

Treatment approach and goals

Treatment aims to reduce symptoms and improve quality of life, focusing on patient self-management, which is why establishing a collaborative therapeutic relationship is essential.

An important step is to acknowledge the impact of CFS/ME on the individual's ability to work, maintain relationships, undertake basic self-care, and maintain self-identity. Frustration and anxiety can arise if there is skepticism towards CFS/ME patients - who may not appear ill - from their family, friends, and medical practitioners.

Miss C and her mother feel the diagnosis makes sense. You explain that you would like to work with Miss C to find ways of managing her symptoms to allow her to participate as much as possible in school and social life.

You arrange an extended follow-up consultation next week with Miss C and her mother to discuss treatment strategies, offering them information to consider before you meet again.

Symptom-specific treatments

The specific treatments that can help include:

- Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT).

- Graded exercise

- Lightning Process (for children 12 to 18). There is encouraging evidence from a small RCT in children.4 It has also been used successfully in young adults but has not been studied in RCTs in older age groups.

Activity pacing, where participants are not asked to increase activity beyond their current perceived energy envelope, has not been shown to be effective for fatigue reduction in large trials and systematic reviews.1,3 Part of the problem may be that pacing has been very variably defined: in the large PACE trial, 3 which was negative, participants were asked to limit their exercise to 70% of their perceived energy envelope; other trials that suggest there may be benefit have used higher figures and/or included co-interventions.1 With the above caveats about how to define pacing, there is limited trial evidence that pacing may increase physical functioning and reduce depression and anxiety.1

Graded exercise on the other hand, where patients are encouraged to increase their activity beyond current functioning, has been much more clearly shown to be effective for both fatigue and physical functioning,1,3 and CBT also has a solid evidence base.

Post-exercise malaise; This is the most feared symptom of many patients with CFS/ME. There was reduced post-exercise malaise in the CBT and GE groups in the PACE trial.3 The fact that CBT can help does not imply that the condition has a psychological cause.

Tips for optimising patient care

- Use written materials and ask patients to bring a support person to appointments (many patients have short-term memory problems).

- Ask the patient to write down their most troubling symptoms and agree on which ones to focus on (avoid overloading the patient).

- Plan ongoing assessment over multiple visits.

- Start low and go slow with medications.

Diet and supplements

There is no evidence-based diet for CFS/ME.

Some practical suggestions patients may wish to try are:

- Ensuring a balanced diet, particularly a Mediterranean diet, which probably helps fatigue in other conditions.

- Small frequent meals, particularly where there is weight loss or difficulty eating larger regular meals.

- Patients with orthostatic symptoms or low blood pressure can try increasing salt intake (a pinch every 2-3 hours).

- The following are sometimes recommended but have no randomised trial support to date. Cost and effort need to be considered, given the absence of evidence:

- Magnesium at bedtime may help with relaxation and pain.

- Co-enzyme Q10 may help with myalgia.

- Vitamin B12 injections have been used but limited evidence.

Pain management

As with other symptoms, treatments for pain must be individualised, and non-pharmacological methods should be considered alongside medications.

A general rule is to start low and slow, as CFS/ME patients can be hypersensitive to medications.

The most likely effective agents are tricyclics, and gabapentin or pregabalin, though beware of exacerbating daytime sedation.

There is no current evidence for low-dose naltrexone, although some advocacy groups recommend it.

Treatment for depression

Behavioural activation is the most effective treatment for low mood. This includes increasing pleasurable activities, connecting with friends and family, and physical movement (necessary caution here).

Antidepressants can be important for people with CFS experiencing depression or anxiety. Depression and anxiety are associated with some patients with CFS. The prevalence of depression was 34% in the baseline measures for the PACE trial.3

Sleep management

In addition to standard sleep hygiene measures, patients with CFS/ME may benefit from targeted sleep advice, including:

Check for a specific diagnosis with a tool such as the brief sleep questionnaire

Targeted use of medications, taken early enough that sedation takes effect around bedtime. For example, taking tricyclics five hours before bedtime.

Low-dose mirtazapine 7.5 mg to 15 mg may be helpful, but no trial evidence exists. There is a risk of weight gain.

Low-intensity behavioural treatments

Low-intensity alternative delivery methods for evidence-based care (e.g., telephone, internet, brief primary care visits, and guided self-instruction of CBT programmes) suggest comparable improvements in physical functioning, fatigue, and patient satisfaction compared to usual care.

In a study on adults, home-delivered (in-person nurse visit or telephone coaching) 'pragmatic rehabilitation' intervention for 20 weeks improved self-reported fatigue compared to supportive listening or treatment as usual.

Miss C and her mother return to see you with a list of the most concerning symptoms: fatigue and poor sleep. The pain is troublesome, but Miss C feels this would improve if her sleep and energy improved.

You discuss a programme of an individualised ME/CFS physical activity or exercise programme designed for people with ME/CFS, for example, if they feel ready to progress their physical activity beyond their current activities of daily living or would like to incorporate physical activity or exercise into managing their ME/CFS.

You stop the tramadol for pain and agree to review the symptoms (particularly pain) again in four weeks.

You talk to Miss C about low-intensity behavioural treatments and she decides to work with you on guided self-instruction on CBT programmes with some graded exercises.

Given her age, her mother is interested in the Lightning Process4 so she will seek local providers and the cost.

She will also see if any CBT therapists specialise in CFS/ME therapy.

Support

Resources for clinicians

To the best of our knowledge, no hospital departments exclusively manage ME/CFS. CBT is usually conducted by Clinical Psychologists, graded exercises by physiotherapists, and there are private fully trained Lightning Process therapists.

(NB: The NICE guidelines are quoted as a source of information. For this condition, they have been severely discredited by world experts in the condition.2)

Resources for patients

What support is available for patients with chronic fatigue syndrome?

We suggest buyer beware here. Some New Zealand and overseas patient support groups only recommend Pacing. Where Pacing encourages maintaining activity to 70% of perceived energy level, it is likely to be ineffective based on the largest trial to date.3

If Pacing is supported, higher targets for perceived energy expenditure are needed, but the evidence is not strong. GET or CBT should be first line management since there is good evidence for both.

Some patient groups also recommend Vitamin B12 injections which do not have a strong evidence base.

We acknowledge that some individuals may feel they benefit from such interventions. We recommend caution.

Useful patient resources include:

Myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME) support Healthify

Tiredness and fatigue Healthify

This MedCase was written by Professor Bruce Arroll, General Practitioner, with review by Professor Paul Little of Primary Care Research at the University of Southampton UK.

References

Recognition of Learning Activities

Don't forget to log your time with The Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners portal for recognition of learning activities.