The 2019 GINA update1 and 2020 NZ Adolescent and Adult Asthma Guidelines2 recommend that budesonide/formoterol is preferred to short-acting beta2-agonists (SABAs) as reliever therapy in adolescents and adults with asthma, across the spectrum of severity.

The term anti-inflammatory reliever (AIR) therapy is used to describe the use of budesonide/formoterol in this way, either as monotherapy (no maintenance therapy) or together with regular scheduled budesonide/formoterol, which is commonly referred to as SMART (SMART: Single combination ICS/LABA inhaler Maintenance And Reliever Therapy).

This MedCase offers a framework for managing asthma in adolescents using the new guidelines.

You receive a discharge summary describing a short stay in the emergency department (ED) by your patient, Mr H, for an exacerbation of asthma.

This is surprising; Mr H is a 14-year old Māori boy with mild asthma who has never previously required hospitalisation.

Mr H has a history of mild asthma diagnosed at age 6. He was treated several times at your practice with salbutamol for wheeze following respiratory infections. There have been multiple repeat prescriptions for salbutamol, becoming less frequent in recent years. Mr H has never had a spirometry test or been prescribed an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS).

The discharge summary states that Mr H responded well to salbutamol via spacer. He was discharged home with a prescription for oral prednisolone and a Symbicort inhaler, and advised to see his GP. Your nurse called his Mum earlier today and arranged an appointment this afternoon.

Mild asthma…. and not-so-mild morbidity and mortality

Hospitalisations for exacerbations of so-called ‘mild’ asthma are common and occur more frequently in Māori and Pacific patients at all ages.3 Patients are usually considered to have mild asthma if their symptoms are well controlled with infrequent use of salbutamol or an ICS.4 However, as discussed in a 2020 webinar with Dr John Kolbe, mild asthmatics account for up to 40% of ED asthma presentations and many asthma-related deaths; up to 1/3 of asthma-related deaths in children occur in those classified as mild.

Despite targeted strategies to reduce disparities, large inequalities in asthma outcomes persist for Māori and Pacific patients, who experience 3-fold higher rates of hospitalisation for asthma than non-Māori or Pacific people.

Children are less likely to be prescribed preventer therapy or to have an asthma control plan or peak expiratory flow (PEF) meter if they are Māori and Pacific, resulting in poorer overall control.5

Mr H and his Mum arrive for their appointment. Mr H is feeling better today with no shortness of breath or wheeze. He is speaking full sentences and he examines normally.

You ask about the recent symptoms. He tells you that after a few days of runny nose and sore throat, he started to feel tight-chested. He found an old salbutamol inhaler but couldn’t find a spacer, so he took two puffs directly from the inhaler. This helped a bit, but overnight his symptoms got worse and he took a lot more salbutamol overnight. When his Mum checked on him in the morning she was worried and took him to the ED, where he was given salbutamol via a spacer plus a dose of prednisolone. His symptoms improved over the morning and he was discharged home.

His Mum asks you why this happened. She is worried that his asthma is getting worse.

You agree, and explain that the recent attack means treatment should be increased.

A new inhaler, Symbicort, is prescribed to give better control of his symptoms as it can be taken regularly for maintenance as well as used as-required for symptom relief.

Anti-inflammatory reliever-based therapy

Symbicort is a good choice for Mr H, as it can be used for both relief and maintenance.2 As-needed ICS/formoterol is more effective and safer than as-needed short-acting beta-2 agonist (SABA) for symptom relief, at all levels of asthma severity.5

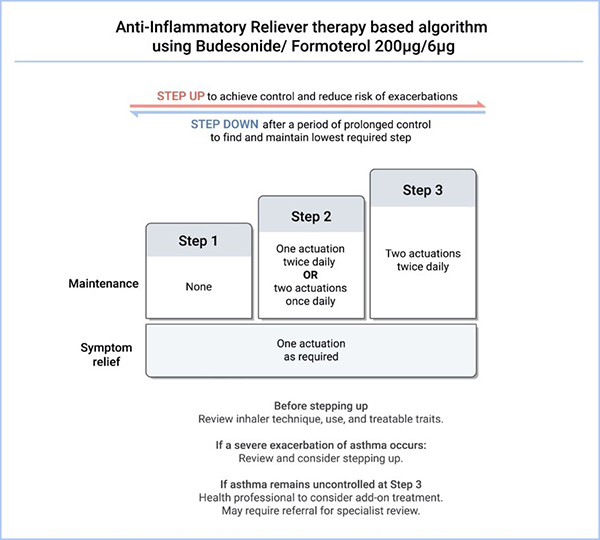

(Figure 1: Anti-inflammatory reliever therapy with budesonide/formoterol 200ug/6ug, from the 2020 NZ Asthma Guidelines2

*Treatable traits refer to overlapping disorders, comorbidities, environmental and behavioural factors that contribute to poor asthma control.)

The New Zealand adult and adolescent asthma guidelines2 follow the 2019 GINA update1 in recommending an ICS/formoterol inhaler as required for relief, with or without regular maintenance therapy, depending on asthma severity.

A single actuation of the 200ug/6ug Symbicort Turbuhaler is recommended for reliever use as-needed at all steps; as sole therapy at Step 1, and together with maintenance doses of one or two actuations once or twice daily at Steps 2 and 3 (SMART regimen), according to symptoms and patient preference. Patients can move up or down the steps as required to maintain control of their symptoms.2

Treatment with regimens that use the SABA for relief alongside maintenance ICS or ICS/LABA are considered second-line therapy but may be used if patients are well controlled and prefer this regimen. However, monotherapy with a SABA for as-required symptom relief is no longer recommended in the long-term management of adult or adolescent asthma.1

Notes on available inhalers:

- At the time of writing (June 2020), only the budesonide/formoterol Turbuhaler (brand name: Symbicort) is available in New Zealand for use as a reliever, either alone or according to the SMART regime.

- The budesonide/formoterol metered-dose inhaler (MDI; brand name: Vannair) is available in New Zealand for maintenance use, but is not currently licensed for use as a reliever.

- Formoterol is the only long-acting beta agonist (LABA) suitable for dual maintenance and relief therapy, due to its rapid onset of action; salmeterol (the LABA in Seretide) has a slower onset making it unsuitable for reliever use; see the 2020 webinar with Dr John Kolbe for further details.

You show Mr H the Asthma & Respiratory Foundation's SMART Asthma Action Plan to show how Symbicort can be used for both relief and maintenance treatment. You ask Mr H if the hospital team gave him an action plan like this; he can’t remember. You ask how he likes the Turbuhaler.

He says he hasn’t tried it yet, then admits he hasn’t collected his medicines from the pharmacy, as he was feeling okay and didn’t think he needed regular treatment.

Health literacy and asthma outcomes are intimately linked

Many New Zealanders - and up to 80% of Māori - have poor health literacy (the ability to find and understand information to make informed and appropriate health decisions), which is associated with reduced use of asthma medications and poorer health outcomes overall.5 A goal for clinicians is to focus on building skills and knowledge of individuals, their whānau and communities to improve health literacy (see Upfront: Understanding health literacy bpacnz ).

Regular assessments

Regular reviews are essential to assess asthma symptoms, control and the risk of future events.2 Note that symptomatic patients can should be assessed after 8 weeks of initiation of, or increase in baseline treatment with an ICS or ICS/LABA; book a follow-up 8 weeks after starting or increasing maintenance therapy.

Assessments should involve some or all of the following, as per the NZ guideline:2

- Symptom assessment. Symptoms are frequently under-reported so consider using the Asthma Control Test (ACT) for children (aged 4-11 years) or adults (aged 12+); a symptom diary for children; or questions from the Australian Asthma Handbook.

- Assessment of the risk of future adverse outcomes, as per Table 3 in the NZ guideline.

- Checking inhaler technique. Poor inhaler technique is an important reason for poor symptom control. Observe the patient’s technique at EVERY consultation, and consider patient preference and ability when selecting an inhaler.

- Check adherence.

- Check for understanding of the inhaler regimen, and use apps, diaries or dispensing records to confirm adherence.

Asthma in adolescents

Asthma symptoms can change in adolescence, getting worse or better.5 It is a time of increased risk-taking behaviours, such as smoking or vaping, and decreased adherence to asthma therapy. Close monitoring is essential, using an approach that empowers adolescents to take responsibility for their health.1

Tips for empowering adolescents to manage their asthma

- Offer the opportunity to attend all or part of the consultation alone.

- Use the HEADSS assessment to identify other health or social issues or questions.

- Simplified treatment regimens are preferred to improve adherence.

- Ensure the patient knows how to arrange follow-up appointments.

- Consider involving a practice nurse as a coach.

- Use apps to aid information sharing and decision making about asthma. Health Navigator NZ has a review of apps, including:

- the free My Asthma app, developed by Asthma and Respiratory Foundation NZ

- AsthmaMD which is also free, but uses different asthma action plans to those used in NZ

- Hailie, which requires paid subscription.

You tell Mr H that you can understand why he thought he didn’t need any further medicine, given that he’s feeling so much better. You ask if he would like to know more about why he needs treatment.

He says he doesn’t really know why he needs another inhaler, as his old blue inhaler didn’t make much difference.

You explain that the new inhaler is different, because it contains medication to help when he feels short of breath, as well as medication to reduce inflammation in the lungs and help prevent another attack. Mr H says this sounds good.

Putting anti-inflammatory reliever therapy into practice

Patients who rely on and trust their salbutamol may be reluctant to switch therapy or have questions about the use of the budesonide/formoterol inhaler. Some common points to discuss at the initiation of budesonide/formoterol reliever therapy, either as monotherapy, or together with maintenance budesonide/formoterol therapy (SMART regimen as with this case) are:

- It can be helpful to highlight the convenience of a single ‘2 in 1’ inhaler.

- The budesonide/formoterol combination is more likely to deliver the correct amount of anti-inflammatory therapy, since the dose of preventer increases each time the inhaler is used for relief.

- Only one actuation of budesonide/formoterol is required for relief; 6ug of formoterol is equivalent to 2 x 100ug of salbutamol.

- Patients may ask if they should return to using their SABA if they have a severe attack. The answer is no, and in fact the budesonide/formoterol is more effective for an acute attack due to the additional budesonide delivered.

You ask if Mr H knows how to use the new inhaler; he doesn’t. Together you watch a video showing how to use a Turbuhaler, and Mr H says he feels ok to give it a try. You arrange an appointment with your nurse later that week to check how he’s going.

Next, you discuss the regimen. You explain you would like him to take two puffs of Symbicort every day for maintenance (as he is at Step 2 of the treatment algorithm), but he can choose to take them together in the morning or in the evening (depending on whether his symptoms are worse during the day or at night), or one puff in the morning and one puff at night. Mr H says he would rather take two puffs every morning.

You then explain that he needs to take one puff of Symbicort for relief when needed. Mr H asks if he should also take his salbutamol inhaler. You explain this is not necessary, and that Symbicort will do a better job of relieving his symptoms.

Together, you complete a SMART Asthma Action Plan, detailing 2 doses of Symbicort every morning, and 1 dose when needed to relieve symptoms. You ask him to book a same-day appointment if he gets to the ‘Severe’ category. You also show Mr H the My Asthma app, which he says he will download.

You ask Mr H to come back to see you in 8 weeks so you can check if the Symbicort is working, and together you book the follow-up appointment. You also signal that you may consider doing a test of his lung function (spirometry) in future, but for now you will focus on getting the symptoms under control.

You ask if Mr H has any other questions. He says he’s okay for now and leaves your office with a new prescription.

Key practice points

- Anti-inflammatory reliever (AIR) based therapy is preferred for all asthma patients, as it is more effective and simpler than SABA-based therapy.

- Budesonide/formoterol (Symbicort) is currently the only ICS/formoterol combination available in NZ; the Turbuhaler is currently the only available formulation.

- Symbicort 200ug/6ug strength is preferred to reduce treatment complexity and allow standardised dosing across different treatment steps.

- Only one actuation of Symbicort is needed for relief.

- Asthma can change during adolescence; monitor closely.

- Poor health literacy and how it may affect asthma management. Use patient aids including videos, apps and printed material to ensure understanding of symptoms and management.

This MedCase was written by Dr Vicki Mount, BSC/BCom, MBChB, MRNZCGP, DipPaeds, with expert review by Professor Richard Beasley, Medical Research Institute of New Zealand, Wellington.

References

MedCase is supported by

Recognition of Learning Activities

Don't forget to log your time with The Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners portal for recognition of learning activities.